Social Contract

An influence of the Revolution, but not of the country

This is series is on the foundations and Founding Fathers of the United States. Follow this link to the first article in the series.

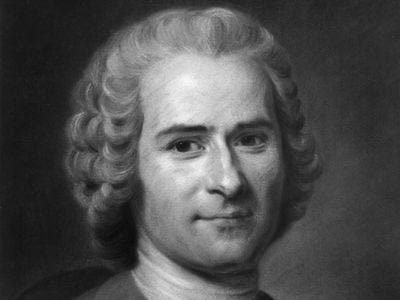

French Enlightenment philosopher and polymath, Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712-1778) wrote on a wide variety of topics, including education, economics, psychology, drama, and music, for which he developed a new system of notation. His best-known works centered on political thought. He remains one of the most important theorists of so-called positive liberty, a theory that proposes individuals must be encouraged or even coerced into being free.

Rousseau was born in the Republic of Geneva, which was at the time a city-state associated with the Swiss Conferacy and now a canton of Switzerland. Since 1536, Geneva had been a Huguenot republic and the seat of Calvinist Protestantism and Rousseau’s family had lived there five generations since an ancestor who might have been a bookseller publishing Protestant tracts, had escaped persecution from French Catholics by fleeing to Geneva in 1549, where he became a wine merchant.

Rousseau was proud that his middle-class merchant family had voting rights in the city. Throughout his life, he generally signed his books “Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Citizen of Geneva”. Althought theoretically governed democratically by its male voting citizens, a small number of wealthy families making up the Council of Two Hundred, who they delegated their power to a 25-member executive group from among them called the “Small Council”.

That city would remain an ideal for him, lionized in his political writings, particularly for its austere virtues, military prowess, and classical republican spirit. He built his political thought around two ideas common to many Enlightenment writers: the state of nature and the social contract.

It should be noted Rousseau differed from Hobbes and Locke, believing the state of nature was a utopia and civilization was a step down from it. In Discourse on the Arts and Sciences and Discourse on the Origin of Inequality, Rousseau argued civilization and material progress separated mankind from the state of nature, causing vanity, jealousy, luxury, feminization, and vice. According to Rousseau, everyone was equal in he state of nature. Tragically, civilization and commerce divide us from one another, creating inequality.

Rosseau saw few solutions to this problem, and dreaded any advance of civilization. He agreed with many theorists in the ancient world who argued liberty could only be preserved under conditions of austerity, rejecting the notions of modern liberty then coalescing around commerce, material progress, and self-interest, feeling only a rigorous program of civic education and communal moral life could delay the encroachment of civilization and the vices following in its wake.

Rousseau’s search for alternatives to modern liberty led him to both praise the ancients and write his most important political text, The Social Contract (1762).

This work argued individuals enter into a social contract in an attempt to conserve what they can of their natural goodness. The Rousseauan social contract isn’t an agreement to form a government, but an agreement to form a civil society of under a set of morals, religion, education, manners, family life, and economics.

“In order then that the social compact may not be an empty formula, it tacitly includes the undertaking, which alone can give force to the rest, that whoever refuses to obey the general will shall be compelled to do so by the whole body. This means nothing less than that he will be forced to be free.” Rousseau

The general will is one of the most difficult of Rousseau’s concepts, but also the most central. The general will isn’t identified with the combined of individual wills of those comprising society, but the will of the community as a whole. Society is viewed as something like a wise parent, whose good sense is ultimately internalized in each of us. Under the tutelage of society, the child is freer to live without conflict. The individual isn’t seen as more limited by society’s structure. Each of us must seek to understand its lessons and when individuals discover our desires conflict with the general will, we are obliged to alter our desires. When those around us discover improper desires in us, it is their duty to correct us. Even an aristocracy of the wisest people should be obliged to obey the general will, rather than their own wisdom, because the general must be the master of us all.

As a libertarian, I can’t easily agree with Rousseau. Society isn’t anywhere analogous to a parent. I’m constantly surprised by what some people in society believe. It certainly doesn’t seem like good sense to me. How do you recognize an opion or a course of action as representative of the general will? Looking at history, the general will has often served as an invitation to the power hungry and the unscrupulous to do whatever they want. No historical event ever epitomized this quite so much as the French Revolution, when Rousseau’s ideas were invoked incessantly to dismantle the tyranny of the old regime and to supplant it with an even more bloodthirsty tyranny of its own. Although Rousseau distrusted all polities larger than the city-state and who have rejected mass nationalistic projects, subsequent advocates of nationalism found Rousseau’s notion of the general will extremely appealing, and that has lead to a lot of very negative consequences to populations around the world.

Great Philosophy, Frightening Details

Moving from the abstract to the particular, Rousseau’s prescriptions in social policy strike libertarians as abhorrent. They’re terrifying when combined with Rousseau’s incessant use of the word “liberty”. In the name of liberty, Rousseau called for censorship of the press, closure of theaters; institution of consumption laws, and a mandatory state religion. Rousseau taught limits to government power were in vain. Only virtue should guide the people who would serve—undivided—as the legislators. “The laws are but registers of what we ourselves desire.” Rousseau wrote, and limits were therefore unnecessary.

The rulers are somehow smarter than you are. Trust them. They’d never lead you astray.

Rousseau’s clear, affective style made him deeply influential, and his invocations of “liberty” inspired many, despite the contrarian nature of many of his ideas. The opening lines of the Social Contract are a striking example:

Man was born free, and everywhere he is in chains. Those who think themselves the masters of others are indeed greater slaves than they.

This ringing endorsement of “freedom” brought courage to many who were suffering under the French monarchy, making Rousseau famous as the educated public read Rousseau’s books in record numbers. His novel La nouvelle Héloise enjoyed great commercial success, as did his book-length treatise Emile, which proposed a system of education to inculcate Rousseau’s philosophy. The subversive section on natural religion “Confession of Faith of a Savoyard Vicar.” would see Emile burned in both Paris and Geneva.

Personal Life & Legacy

Rousseau’s life lived as he thought, with a paroxical and tempestuous personal life. He had several sexual affairs with women before somewhat settling down with Therese Levasseur, a servant. According to his Confessions, Rousseau fathered five illegitimate children with Therese and placed all of them in an orphanage. Rousseau wrote he persuaded Thérèse to give each of the newborns up to a foundling hospital, for the sake of her “honor”. In reality Rousseau found Therese and her family to be “ill brought up and thought the foundling hospital would be better than their mother’s care. He did eventually enter into common law marriage iwth Therese and eventually, Rousseau inquired about the fate of his son, but no record could be found. When Rousseau subsequently became celebrated as a theorist of education and child-rearing, his abandonment of his children provided fodder for Voltaire and Edmond Burk to roundly criticize his ideas.

Rousseau eventually came to mistrust all around him, including the philosopher David Hume, who had offered him refuge in England when the French authorities became concerened about his thoughts. Rousseau’s Confessions, published posthumously, were scandalous enough some of his admirers claimed they were forgeries.

Rousseau is chiefly known today for his works, primarily because the American revolutionaries loved his invocation of “liberty” but also seemed to recognize he was quite ready to betray liberty as they understood it. Had there been no United States after the French Revolution, Rousseau might well be remembered as the man who destroyed liberty forever.

Rousseau influenced the American Founders in a mixed and complex way. Thomas Jefferson was clearly influenced by his ideas, especially the concept of popular sovereignty. Meanwhile, John Adams was critical of his more radical views, particularly after the French Revolution. Many Founders were more heavily influenced by Locke and Montesquieu, but Rousseau’s emphasis on the “general will” and the people’s right to rule still played a significant factor in the American democracy, though ultimately expressed in a more moderated, representative form. Thomas Jefferson’s famous line, “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal,” directly reflects Rousseau’s ideas found in The Social Contract.

Certainly, Rousseau’s assertion that the ultimate political power rests with the people, was adapted by the Founders into the system of representative democracy used in the United States.

Rousseau argued the right to rule is granted by a social contract with the people and can be broken if rulers become oppressive. Clearly, that influenced the Declaration of Inedependence and can be seen in the US Constitution’s system of separated powers designed to prevent the concentration of power. John Adams sharply criticized Rousseau’s philosophy, calling him a “Coxcomb” and a “Fool” in his writings. Adams’s dislike for Rousseau grew significantly after the radical turn of the French Revolution, which he saw as a dangerous embodiment of Rousseau’s ideas.

The American Founders tended to be much more pragmatic than Rousseau, ultimately framing a system of representative democracy rather than the direct democracy Rousseau advocated for.

Rousseau himself died of a stroke in the early years of the American Revolution and never got to see what his ideas influenced, nor object to how subsequent events colored how his admirers adapted his ideas.